(Puts on media critic hat.)

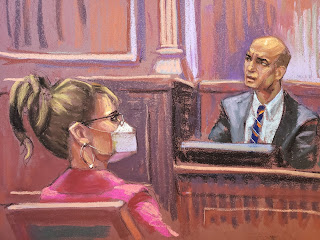

I don’t think Sarah Palin will or necessarily should prevail in her libel suit against the New York Times, owing to the extremely high bar the law sets, saying one must prove “actual malice” (a virtual impossibility) or reckless disregard for the truth.

But it’s a lot closer than most people care to admit.

Even as a once-and-kinda-still journalist and free speech maximalist – and, I should disclose, a former Times company employee who still holds a pension with them – I will commit the apostasy of opining that it might be time to rethink if, when and how media outlets should be held responsible for the false information they publish, whether with malice or in error.

Times defenders in the case point out they acknowledged the error and posted a correction. That’s well and good. (Though the old version of the editorial actually remained up on the website for some time after.)

The facts of the case, though, show that they did not take any pains to establish the authenticity of what they printed before they did. The editorial editor, James Bennett, inserted the clearly false and libelous assertion after it had been edited but right before it was published. By his own admission, he did not research or fact check it before doing so. Even though high-level Times colleagues pointed out the falsehood minutes after it was published, they waited to address it until the next morning. After some exchanges, the editor admitted, “I don’t know what the truth is here.”

Call me old-fashioned, but that sounds pretty reckless disregard-y to me.

Add to that, the Times itself had run stories some years earlier establishing the lack of any connection between the Giffords shooting and the Palin election graphic, and the editor had overseen similar pieces published at an earlier publication. The “I just didn’t know” defense becomes stretched further and further beyond the point of plausibility.

I don’t want to see U.S. libel laws swing so far as the British system, which puts the onus on the publisher rather than the subject to establish veracity. But under our current legal framework, essentially the worse a journalist you are, the thicker your armor grows.

(Let us not forget, NYT vs. Sullivan, the landmark case that forms the base of current American libel law, also involved an egregious error against an elected official – though it was actually in an advertisement, not editorial copy, something most people forget.)

As it stands now, journalists can f*ck up to infinity and never be held to account. All they have to do is wave the white flag of, “I’m really bad at this!!!” in the form of a correction, and it’s a get-out-of-jail-free card.

Oftentimes it takes the threat of a lawsuit like this one to evoke a correction at all. I don't know of any other industry where you can be terrible at your job and cause actual harm to others, and all you have to do is say "whoops" to be absolved of any duty to compensate.

The New York Times screwed up badly in their editorial, and unquestionably libeled Sarah Palin. She’s not a figure particularly beloved by me, but the day we start adjusting our standards over media responsibility based on the popularity of who they wrong is the day the moral foundation of the whole fourth estate goes out the window.

So when should media outlets pay – quite literally – when they commit egregious, easily preventable errors like this? I don’t know the answer to that. Maybe it depends on the speed and willingness with which they’re able to own up to and fix the mistake. In the old days, that might have been a few days, but now it’s probably hours.

James Bennett and the Times knew, or should have known, right away that they had published false and libelous information about the former Alaska governor and veep candidate. Rather than taking action, they literally slept on it.

All I do know is this whole episode does not reflect well on the modern state of journalism. All the big voices have come out to back the Times, partly because most mainstream platforms loathe Palin (and don’t even bother to hide this fact) but mostly because they're scared of the prospect of having to write hefty checks when they inevitably make mistakes, too.

Somewhere there’s a perfect middle where journalists aren’t hampered by a chilling effect of fearing being hauled into court by every sheriff or civil bureaucrat who doesn’t like what they wrote, but also have to pay the piper when their shoddy work causes harm to others. Hopefully not Gawker-destroying amounts for honest mistakes... but something.

Every (good) media outlet has published countless stories about

businesses, governments or individuals who commit foul deeds and escape any

real responsibility for it, rightly holding these up as acts of injustice.

Journalism should hold its own industry to the same standard.